I recently returned from three days of coaching at Nintex in Kuala Lumpur. During this time, I had the opportunity to work with six teams consisting of 40 people. What struck me most during this experience was the level of trust Nintex showed in me. Despite the inability to micromanage my coaching, they placed their trust in my expertise. This trust is foundational for effective coaching and collaboration.

One topic we discussed extensively was the concept of “Order Point,” a key element in the Kanban methodology for replenishing backlogs just-in-time. Unlike traditional approaches such as planning at the start of an iteration (common in Scrum), the Order Point enables teams to dynamically manage their workload based on demand.

Understanding Order Point

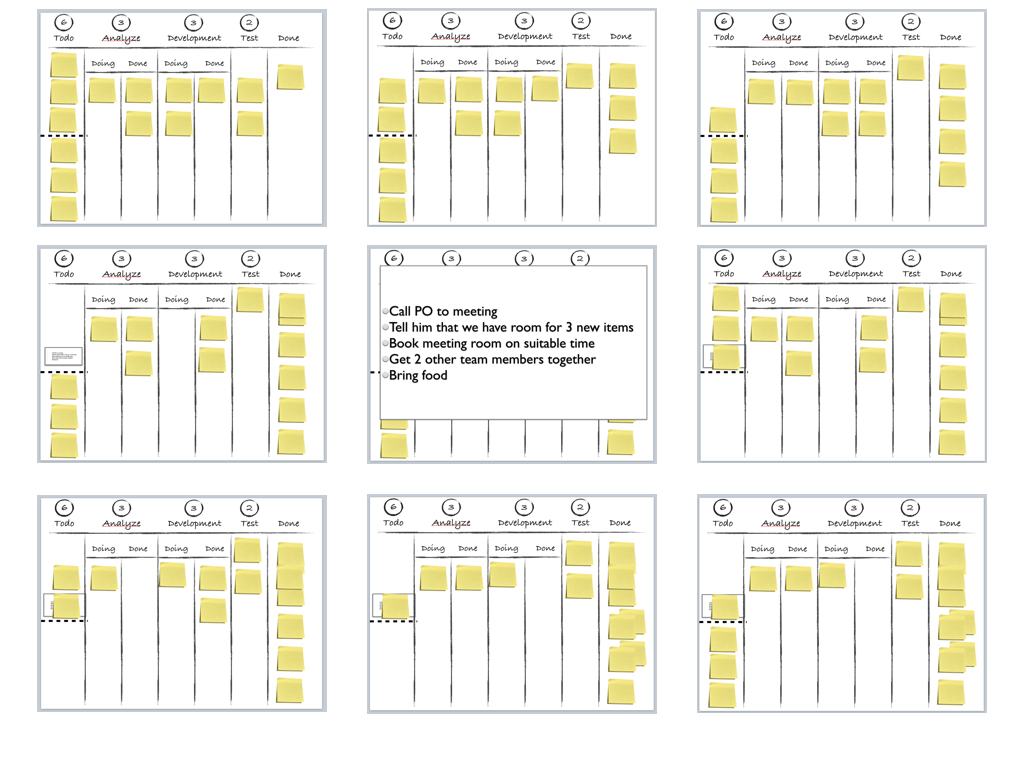

The Order Point, as described in Kanban In Action, serves as a signal to replenish the backlog when it reaches a predetermined threshold. This threshold, illustrated in the accompanying cartoon, represents the point at which new work items are needed to maintain workflow efficiency.

Here’s how it works:

- The backlog (Todo) has a predefined work in process (WIP) limit of 6 items, with an Order Point marked at the third item.

- Work items are pulled from the top of the backlog as teams progress.

- When the third item is pulled, a kanban card signals the need to replenish the backlog.

- The card prompts communication with stakeholders to obtain more work items.

- Meanwhile, the team continues working on existing items until the backlog is refilled.

- This process ensures a steady flow of work without overburdening the team or creating idle periods.

Implementing the Order Point technique raises questions about traditional planning practices. By decoupling replenishment from fixed timeframes, teams can adapt more flexibly to changing priorities and demand. However, it’s essential to assess the impact on lead time, flow efficiency, and overall process effectiveness.

In conclusion, while the Order Point offers significant benefits in workflow optimization and waste reduction, its implementation requires careful consideration of context and implications. Teams should strive for a balance between responsiveness and stability, leveraging Kanban principles to drive continuous improvement.